The Fowler-Finn Lab at Saint Louis University investigates how temperature affects vibrational communication in insects.

For this investigation, the researchers manipulate temperature in the lab to study changes in communication and interactions between individuals under different thermal conditions.

For example, listen to the differences in treehopper song pitch and frequency when recorded at 17°C (63°F) versus 24°C (75°F).

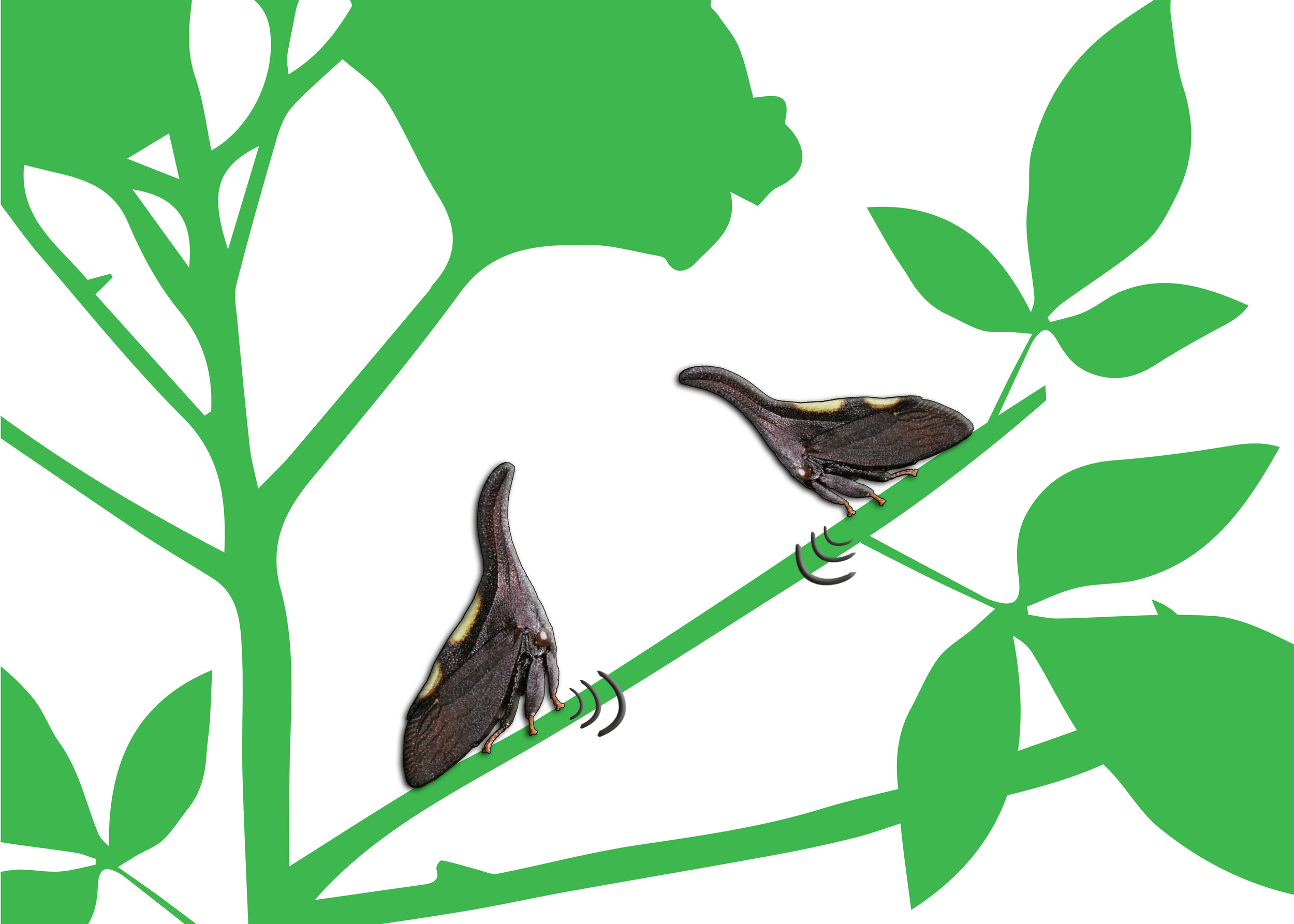

For this study, the Fowler-Finn lab is focusing on treehoppers, which find mates through a complex set of behaviors. Males fly from plant stem to plant stem and produce vibrations when they land. If a female is present and likes what she hears, she will call back. The pair will duet until the male locates the female and attempts to mate. Listen to the duet here.

When the

temperature rises,

many insects will forego their regular activities, like searching for food or attempting to court a love interest. Singing insects like treehoppers face two major challenges for searching and finding mates in the face of global warming:

CHALLENGE ONE

Insects mate within a specific range of temperatures (known as an “optimal temperature range”). When temperatures rise, insects may spend more time in temperatures outside of their optimal range, which means less time available for mating.

CHALLENGE TWO

Insects attract and find mates using song. When temperatures change, songs can change in quality, which may confuse potential mates. The risk with warming is whether these changes in song can lead to a breakdown in mating communication and, ultimately, mating success. For instance, listen to the differences in Ebony bug songs at 18°C (64°F) versus 25°C (77°F).

Understanding the effects of temperature changes on individuals in the lab provides insight into the effects of climate change on insect populations in the wild.

The Fowler-Finn lab is using this study to make predictions about changes in insect communities and extinction risk in a warming world.

Major findings

Global warming poses unknown challenges to the abilities of animals to find and attract mates. We know a range of the traits involved in mating communication are thermally sensitive, but we are only beginning to understand how global warming might affect these traits. This study helped us learn three important things about insect communication in the face of warming:

finding #1

The likelihood of an insect signaling changes as temperatures change:

Insects are not always interested in communicating with potential mates. If temperatures get too hot or too cold, their priority shifts from reproduction to survival, and they become unlikely to signal to a potential partner. In this study, we found that male treehoppers won’t signal to females when temperatures go above 36°C (97°F), suggesting that warming does inhibit mating communication.

Notice the curved shape of the lines you see here. These are called “Performance Curves” and they describe how well individuals perform a function (like signaling to a mate) when exposed to particular temperatures. Our data show that males are mostly likely to signal to a female between 21-36°C (70-97°F). At temperatures above 36°C, they stop signaling (and start dying).

finding #2

chances of mating decline as temperatures rise:

Even when males and females are interested in communication, temperature can still affect other behaviors that determine whether mating occurs. For instance, when temperatures are too hot or too cold, it might be harder for males to move around to find potential mates or to perform the precise movements necessary for successful reproduction. In this study, we found that pairs of male and female treehoppers were most likely to mate at intermediate temperatures.

The shape of this curve is similar to those for the likelihood for males to signal. Male-female pairs were most likely to mate when temperatures were between 21-33°C (70-91°F).

finding #3

Different species are active at different temperatures:

The same temperature can have different effects on different species of insects. For some species, warming creates mating opportunities because the temperatures are enjoyable for a longer amount of time in the day. For other species, warming is a constraint, severely limiting the amount of time they can be active to court potential mates. In this study, we found that different species of treehopper were most active at different temperatures. What was “too hot” for one species was “ideal” for another.

Look how different species function at different temperatures! For Viburnum, females are most likely to signal to males when temperatures are between 21 and 33°C. But for Ptelea, females are most likely to signal between 33 - 36°C.

finding #4

Signals vary in quality across temperatures:

Insects may change their song as temperatures change, which can lead to changes in song quality and attractiveness. In this study, we found that males produce songs with higher pitches at hotter temperatures, which we feared would repel females from wanting to mate with them. Surprisingly, and fortunately, females prefer higher-pitched songs at hotter temperatures, suggesting that warming won’t pose a threat for mating in this species, as long as male songs and female preferences continue to change at the same rate.

Notice the relationship between air temperature and the frequency of male songs. As the temperature warms, the frequency gets higher and higher, until the temperature gets too hot for signaling (around 36°C). In this figure, the dots are the data from the experiment; the dashed line is the model; and the bar surrounding the dashed line is the error surrounding the model (i.e. the dashed line could be anywhere within that bar).

about the lab

The Fowler-Finn Lab at Saint Louis University studies vibrational communication using a variety of arachnid and insect species. This diverse team of researchers explores why insects sing the songs they do, how social and environmental conditions affect these songs, and the future of insect communication in a warmer, drier world.

To learn more about their work, visit FowlerFinnLab.com

The Fowler-Finn lab group, outside one of the SLU greenhouses in which they do their work. Photo credit: Kika Tuff / Impact Media Lab

Graduate student William Shoenberger studies treehopper behavior on a host plant in the greenhouse. Photo credit: Kika Tuff / Impact Media Lab

Graduate student Dowen Jocson observes a mating trial between harvestmen (also known as daddy longlegs) in the lab. Photo credit: Kika Tuff / Impact Media Lab